Related Topics

Leopold II: Belgium 'wakes up' to its bloody colonial past after the killing of an African American by the U.S.A urban Police men:

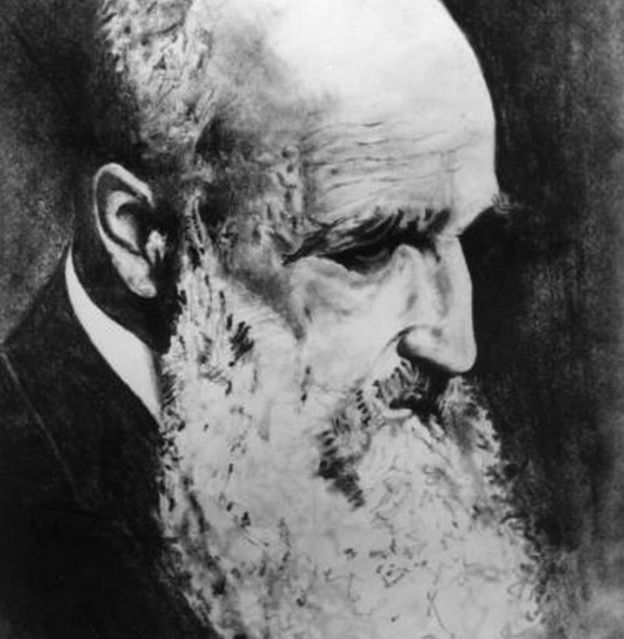

Image copyrightGETTY IMAGES

Image copyrightGETTY IMAGESInside the palatial walls of Belgium's Africa Museum stand statues of Leopold II - each one a monument to the king whose rule killed as many as 10 million Africans.

Standing close by, one visitor said, "I didn't know anything about Leopold II until I heard about the statues defaced down town".

The museum is largely protected by heritage law but, in the streets outside, monuments to a monarch who seized a huge swathe of Central Africa in 1885 have no such security.

Last week a statue of Leopold II in the city of Antwerp was set on fire, before authorities took it down. Statues have been daubed with red paint in Ghent and Ostend and pulled down in Brussels.

Leopold II's rule in what is now Democratic Republic of Congo (DRC) was so bloody it was eventually condemned by other European colonialists in 1908 - but it has taken far longer to come under scrutiny at home.

Image copyrightGETTY IMAGES

Image copyrightGETTY IMAGESLast week thousands in the country of 11 million joined solidarity protests about the killing of US black man George Floyd in police custody.

A renewed global focus on racism is highlighting a violent colonial history that generated riches for Belgians but death and misery for Congolese.

"Everyone is waking up from a sleep, it's a reckoning with the past," explains Debora Kayembe, a Congolese human rights lawyer who has lived in Belgium.

Statues defaced and removed

Like statues of racist historical figures vandalised or removed in Britain and the US, Leopold II's days on Belgian streets could now be numbered.

On Monday the University of Mons removed a bust of the late king, following the circulation of a student-led petition saying it represented the "rape, mutilation and genocide of millions of Congolese".

Joëlle Sambi Nzeba, a Belgian-Congolese poet and spokesperson for the Belgian Network for Black Lives, says the statues tell her she is "less than a regular Belgian".

Image copyrightGETTY IMAGES

Image copyrightGETTY IMAGES"When I walk in a city that in every corner glorifies racism and colonialism, it tells me that me and my history are not valid," she explains from the capital.

For activists the holy grail is the giant statue of Leopold II on horseback at the gates of the Royal Palace in Brussels. A petition calling on the city for its removal has reached 74,000 signatures.

"I will dance if it comes down. I never imagined this happening in my lifetime," Ms Kayembe adds. It would be "really significant for Congolese people, especially those whose families perished," she explains.

She does not believe it will not be quick or easy. There are at least 13 statues to Leopold II in Belgium, according to one crowd-sourced map, and numerous parks, squares and street names.

Warning: This piece contains graphic pictures

One visitor to the Africa Museum, where an outdoor statue was defaced last week, disagreed with the idea of removing them - "they're part of history," he explained.

A king who still commands praise

On Friday the younger brother of Belgium's King Philippe, Prince Laurent, defended his ancestor saying Leopold II was not responsible for atrocities in the colony "because he never went to Congo". The royal palace is yet to give its own response.

For many years Leopold II was widely known as a leader who defended Belgium's neutrality in the 1870-71 Franco-Prussian war and commissioned public works fit for a modern nation.

Image copyrightREUTERS

Image copyrightREUTERSIn 2010, former Belgian foreign minister Louis Michel and the father of future prime minister Charles Michel, called Leopold "a hero with ambitions for a small country like Belgium".

In a TV debate this week, a former president of the Free University of Brussels, Hervé Hasquin, argued there were "positive aspects" to colonisation, listing the health system, infrastructure, and primary education he said Belgium brought to Central Africa.

Colony built on forced labour and brutality

"Civilisation" was at the core of Leopold II's pitch to European leaders in 1885 when they sliced up and allocated territories in what became known as the Scramble for Africa.

He promised a humanitarian and philanthropic mission that would improve the lives of Africans.

Image copyrightGETTY IMAGES

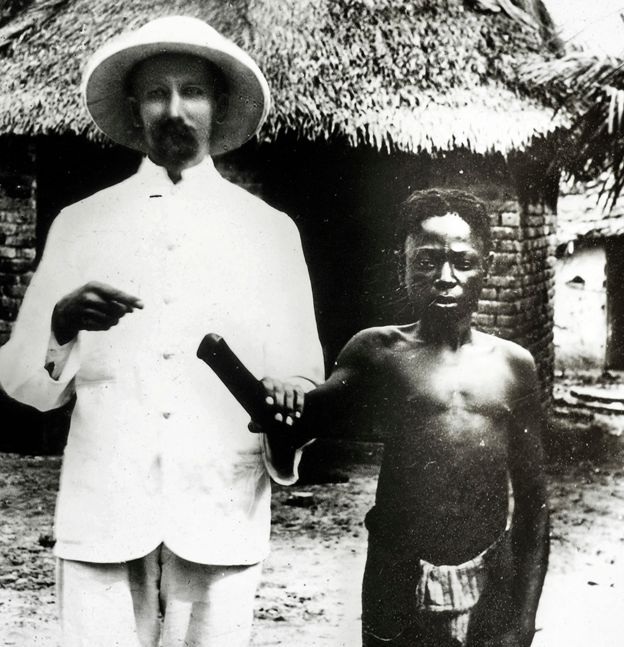

Image copyrightGETTY IMAGESIn return European leaders, gathered at the Berlin Conference, granted him 2m sq km (770,000 sq miles) to forge a personal colony where he was free to do as he liked. He called it Congo Free State.

It quickly became a brutal, exploitative regime that relied on forced labour to cultivate and trade rubber, ivory and minerals.

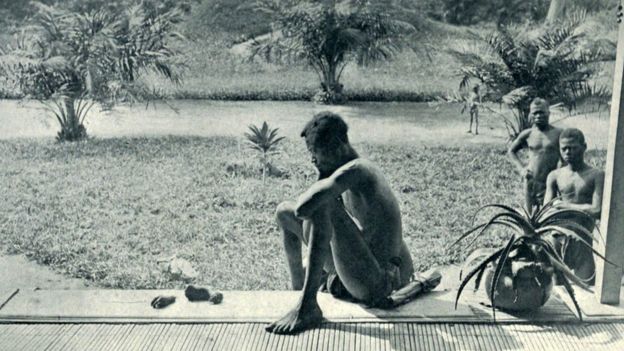

Archive pictures from Congo Free State document its violence and brutality.

Image copyrightALAMY

Image copyrightALAMYIn one, a man sits on a low platform looking at a dismembered small foot and small hand. They belonged to his five-year-old daughter, who was later killed when her village did not produce sufficient rubber. She was not unique - chopping off the limbs of enslaved Congolese was a routine form of retribution when Leopold II's quotas were not met.

Colonial administrators also kidnapped orphaned children from communities and transported them to "child colonies" to work or train as soldiers. Estimates suggest more than 50% died there.

Killings, famine and disease combined to cause the deaths of perhaps 10 million people, though historians dispute the true number.

Leopold II may never have set foot there, but he poured the profits into Belgium and into his pockets.

He built the Africa Museum in the grounds of his palace at Tervuren, with a "human zoo" in the grounds featuring 267 Congolese people as exhibits.

Image copyrightRMCA TERVUREN; A. GAUTIER, 1897

Image copyrightRMCA TERVUREN; A. GAUTIER, 1897But rumours of abuse began to circulate and missionaries and British journalist Edmund Dene Morel exposed the regime.

By 1908, Leopold II's rule was deemed so cruel that European leaders, themselves violently exploiting Africa, condemned it and the Belgian parliament forced him to relinquish control of his fiefdom.

Belgium took over the colony in 1908 and it was not until 1960 that the Republic of the Congo was established, after a fight for independence.

When Leopold II died in 1909, he was buried to the sound of Belgians booing.

Image copyrightALAMY

Image copyrightALAMYBut in the chaos of the early 20th Century when World War One threatened to destroy Belgium, Leopold II's nephew King Albert I erected statues to remember the successes of years gone by.

This makeover of Leopold's image produced an amnesia that persisted for decades.

Calls for apologies

The current protests are not the first time Belgium's ugly history in Congo has been contested in the streets.

In 2019, the cities of Kortrijk and Dendermonde renamed their Leopold II streets, with Kortrijk council describing the king as a "mass murderer".

And in 2018, Brussels named a public square in honour of Patrice Lumumba, a hero of African independence movements and the first prime minister of Congo, since renamed the Democratic Republic of Congo.

Image copyrightGETTY IMAGES

Image copyrightGETTY IMAGESLast year a UN working group called on Belgium to apologise for atrocities committed during the colonial era.

Charles Michel, prime minister at the time, declined. He did however apologise for the kidnapping of thousands of mixed-race children, known as métis, from Burundi, DR Congo and Rwanda in the 1940s and 1950s. Around 20,000 children born to Belgian settlers and local women were forcibly taken to Belgium to be fostered.

What next for the statues?

Statues of Leopold II should now be housed in museums to teach Belgian history, suggests Mireille-Tsheusi Robert, director of anti-racism NGO Bamko Cran. After all, destroying the iconography of Adolf Hitler did not mean the history of Nazi Germany was forgotten, she points out.

Image copyrightAFP

Image copyrightAFPIn Kinshasa, the capital of DRC, Leopold II's statues were moved to the National Museum.

"Leopold II certainly does not deserve a statue in the public domain," agrees Bambi Ceuppens, scientific commissioner at the Africa Museum. But taking the monument away does not solve the problem of racism, she believes, while creating one museum devoted to the statues would not be useful either.

In DRC itself, no-one has really noticed the Belgian protests, says Jules Mulamba, a lawyer in the south-eastern city of Lubambashi. He attributes colonial crimes to the king himself, rather than the Belgian people or state.

Beyond removal of statues, far more work is required to dismantle racism, protesters and black communities argue.

For decades, colonial history has been barely taught in Belgium. Many classrooms still have Hergé's famous cartoon book Tintin in the Congo, with its depictions of black people now commonly accepted as extremely racist.

Belgium's education minister announced this week that secondary schools would teach colonial history from next year.

"It's a good thing that everyone is waking up, looking around and thinking 'is this right?'" says Ms Kayembe.

Additional reporting by Eve Webster in Brussels

The Grave site of an African Kenyan anti-colonial rebel, Dedan Kimathi, has been discovered in the prison premises where the British colonialists secretly buried him after hanging him to death:

That time the British people had great ambitions to take over this whole world and to rule it:

By AFP

26 October, 2019

Mukami Kimathi the now eldery wife of Dedan, poses for a photograph in front of two busts erected in honour of her husband, the late freedom fighter Dedan Kimathi and South African anti-apartheid revolutionary Nelson Mandela at Dedan Kimathi University in Nyeri County on January 16, 2019. NMG PHOTO

In Summary

- In 2007, on the 50th anniversary of Kimathi's death, then president Mwai Kibaki unveiled a bronze statue of the freedom fighter on a street named after him in downtown Nairobi.

- In 2013, Britain compensated more than 5,200 elderly Kenyans tortured and abused during the insurgency.

The grave site of a guerilla leader in Kenya's anti-colonial rebellion has been discovered beneath a prison in Nairobi, a foundation set up by his family says, more than 60 years after he was executed.

Dedan Kimathi, a top insurgent in the Mau Mau uprising that spurred Kenya towards independence from British rule, was hanged in 1957 at Nairobi's Kamiti Maximum Prison.

His body was buried in an unmarked grave, the exact whereabouts of which were long unknown, despite concerted efforts by his family to identify the site.

But a nonprofit established in his name, the Dedan Kimathi Foundation, announced Friday it had found Kimathi's resting place after a years-long search.

"It is with great joy we would like to announce that... the gravesite of liberation hero Field Marshal Dedan Kimathi Waciuri has finally been identified!" the foundation's CEO Evelyn Wanjugu Kimathi said in a statement.

"The development is not just great news for the Dedan Kimathi family but also the larger freedom struggle heroes' fraternity."

Also Read

Uganda Airlines delays flight over glitch

Universities producing ‘robbers’ in Uganda- Dr Vishal Mangalwadi

A video posted on the foundation's Twitter page showed supporters singing and dancing around Kimathi's elderly widow, who has long urged Kenya's government to help find her husband's remains.

His grave was located beneath the prison, the foundation said, without offering further details about how it was found, or identified as Kimathi's burial site.

His family hopes to exhume his remains for burial and is awaiting permission from the Chief Justice of the Supreme Court of Kenya, David Maraga, the foundation said.

Mau Mau fighters battled British colonial rule from 1952 to 1960, paving the way for independence even though the movement itself was defeated in a brutal crackdown.

The guerrillas, mainly drawn from the Kikuyu people, terrorised colonial communities with attacks from bases in remote forests, challenging white settlers for valuable land.

At least 10,000 Kenyans died in the struggle -- some historians say more than double that.

Thousands suffered horrific torture including sexual mutilation, and tens of thousands more were detained in shockingly harsh detention camps, including US President Barack Obama's grandfather.

The capture of Kimathi in October 1956, and his execution by hanging a year later, was a significant blow to the movement.

The insurgency over, Kenya won self-rule in 1963, and full independence the following year.

But while the Mau Mau was a key step towards independence, it also provoked bitter divisions between those who backed the fighters and those who served colonial forces. It remained outlawed until 2003.

In 2007, on the 50th anniversary of Kimathi's death, then president Mwai Kibaki unveiled a bronze statue of the freedom fighter on a street named after him in downtown Nairobi.

In 2013, Britain compensated more than 5,200 elderly Kenyans tortured and abused during the insurgency.

The search in Germany for the lost skull of Tanzania's Mangi Meli

Image copyrightTAHIR DELLA

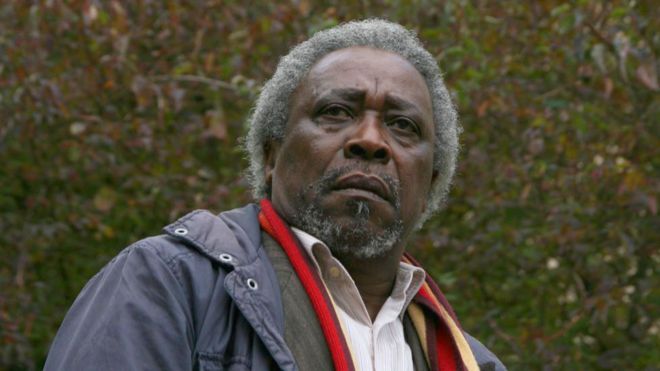

Image copyrightTAHIR DELLAPressure is growing on Germany and the UK to return to Africa skulls taken as trophies and for discredited racial research more than a century ago, writes the BBC's Damian Zane.

A Tanzanian based in Germany, Mnyaka Sururu Mboro, has been searching for the lost skull of Mangi Meli for 40 years.

Mangi Meli, a chief from the north of what is now Tanzania, was executed in 1900 for his role in a rebellion against German colonial rule.

After he died, his body was decapitated and his head was taken to Germany.

The exact whereabouts of his skull are not clear, but the admission by the Berlin-based Prussian Cultural Heritage Foundation (known by its German initials SPK) that it has far more human remains from Tanzania in its archive than previously thought has left Mr Mboro more hopeful.

He is from the same region in Tanzania as Mangi Meli and in 1977, before he left to study in Germany, he promised his grandmother that he would retrieve the skull.

Researchers have found 200 Tanzanian remains in the collection, many of them skulls, that were taken while the country was under German rule, which is more than double the original estimate.

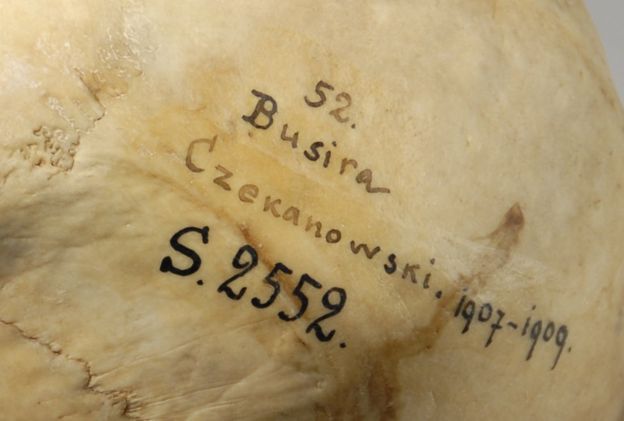

Image copyrightNATIONAL MUSEUMS IN BERLIN

Image copyrightNATIONAL MUSEUMS IN BERLIN

Since October 2017 they have been trying to establish the origins of the bones in the archive, which number in the thousands.

Their project began a year after German journalists uncovered the extent of the remains from the country's former colonies now held by the SPK.

Researchers have also identified 900 skulls from Rwanda, and an estimated 400-500 from Togo and Cameroon - these were all countries that were part of the German empire between 1884 and 1918.

Remains that were taken from Namibia did not make it into the SPK's collection.

Sometimes the skulls were taken as trophies, but more often the human remains were transported to aid with now discredited research into racial classification.

In 1899, German anthropologist Felix von Luschan sent out a message encouraging people to collect remains from the country's colonies saying that "even an amateur can procure anthropological material.

"He should always bear in mind that each single skull that he brings with him is more important than a general description of a type. Any occasion to rescue a large number of skulls from being destroyed in the ground or in a fire should be zealously used, without causing offence.

"The [ethnology] museum will soon be newly sorted in an honourable way and will then be the most beautiful and great monument for our Schutztruppe [German colonial troops]."

Image copyrightNATIONAL MUSEUMS IN BERLIN

Image copyrightNATIONAL MUSEUMS IN BERLIN

The von Luschan collection, which originally contained 6,300 skulls, ended up with the SPK in 2011 after passing through several hands with some of the remains and much of the information relating to the bones having been lost.

The museum body now sees it as its mission to find out the origin of all the skulls and return them if they were taken in what it calls a "context of injustice", for example if the skull belonged to someone who was executed.

Proper burials demanded

Tanzania's Foreign Minister Augustine Mahiga has said his government wants to discuss the return of the remains, but they want to go beyond the SPK's idea of the "context of injustice".

"In my opinion, when you talk about human bodies you talk about human dignity. It's like saying how important is dignity to Tanzania. You don't take someone's body to do research," Abdallah Saleh Possi, Tanzania's ambassador to Germany, told the BBC.

"If there was a context of injustice - such as execution - then you cannot defend it, but even if they were not taken in the context of injustice, who consented that these bodies should be transported?"

And in that light, the ambassador asks: "Why shouldn't these remains be returned? Who needs them there? Why shouldn't they be accorded a proper burial?"

Image copyrightAFP

Image copyrightAFPA proper burial is what is on the mind of Mr Mboro.

He says that if he can return Mangi Meli's skull to Moshi in the north of Tanzania then he "will feel at peace" as the chief's dismembered body needs to be complete.

"They have to bring the remains back to the people who are still suffering from the loss," he adds.

Mr Mboro, who now lives in Berlin, comes from the same community as the executed chief and grew up on the stories of his bravery.

His grandmother told him how he remained defiant up to his death.

Mangi Meli was hanged with 18 other rebels but he took seven hours to die, which was seen as proof of how strong he was, Mr Mboro says.

'Ignorance and resistance'

In 1977, when he was 27, Mr Mboro won a place to study civil engineering in Germany and he made a pledge to his grandmother.

"When I went to say goodbye to her she jumped up and went outside the hut to tell all the villagers to come," Mr Mboro remembers.

"She told them, 'You see my man is going to Germany and he will bring back the skull of Mangi Meli', and I had to promise."

But the village is still waiting.

How Britain purged colonial records towards African independence:

October 16, 2018

Written by Robert Atuhairwe

British colonial soldiers guard suspected Mau Mau collaborators. Operation Legacy sought to hide similar embarrassing documents

As independence approached, the British introduced a policy of purging documents containing details of their activities in the colonies, including Uganda.

This policy, codenamed ‘Operation Legacy’, started in India which got independence in 1947. However, it was not a top-bottom directive that originated in London; rather it was initiated in the colonies to match the circumstances.

The goal was to save the honour of Britain and the local collaborators. An article by Shohei Sato tilted “‘Operation Legacy’: Britain’s destruction and concealment of colonial records worldwide” published in the Journal of Imperial and Commonwealth History last year, says the policy with regard to colonial documents worldwide evolved from “destroy” to migrate”, to “conceal”.

On May 3, 1961, the colonial secretary sent guidance on the disposal of the classified documents to Tanganyika, repeating the message to Uganda and Kenya. However, discussion of the policy seems to have started at an earlier point.

The earliest record that discussed the selection of documents for the purpose of preventing “embarrassment” in Uganda goes back to an earlier date, of April 21, 1960. On February 27, 1961, a letter was sent out to the Treasury in London asking for “an obliterating agent”, one which under any process would not reveal what had previously been written before obliteration.

The next day, presumably before the once in Uganda received a reply from London, a memorandum was sent from the private secretary of the chief secretary of Uganda to all heads of departments ordering them not to hand over to the new government any documents which may: “prejudice the defense of the Commonwealth in the event of war; or embarrass Her Majesty’s Government or any other Government or the present Government of Uganda; or lead to the identification of a source and thereby to the possible victimisation of that source; or provide information which might be used for the victimisation of any person”.

Documents that could be passed on to the new state were called “Legacy papers” or “Legacy files” and the ones that had to be burnt or kept secretly were called the ‘DG’ papers.

DIRTY DOCUMENTS

The symbol “DG” was applied with a rubber stamp in the top right-hand corner of correspondence to distinguish the “dirty” papers. “DG” originally stood for “Deputy Governor”.

This misleading acronym was deliberately chosen: if “dirty” material so marked fell into the hands of unauthorised persons, it could more easily be explained away by saying that it was merely an indication that it was a subject falling within the portfolio of the deputy governor.

The purpose was not only to protect Britain’s reputation but also to remove those papers likely to be embarrassing to African leaders, officials and politicians in the future. Whereas “DG” was used for correspondence within Uganda, exchanges outside he protectorate that were to be kept away from the eyes of unauthorised persons were marked as ‘Personal’.

The general idea was that the operation should only be known to, and carried out by a civil service officer who was a British subject of European descent. Thus, neither “DG” nor “Personal” was a security grading; rather, it was more of a racial indication: both could be “used in conjunction with restricted, confidential, secret or top secret classification” but top secret material was always marked ‘Personal’.

Among the conventional ‘restricted’ documents were those marked “U.K. Eyes Only”, “Guard” (not to be seen by US citizens) and “Personal” (not to be seen by unofficial ministers). Though not much used in Asian colonies, a racial dimension in the operation came to the fore in African colonies.

A case in point: on March 3, 1961, R.E Stone, a graduate of Wadham College, Oxford, and who came to Uganda as a cadet in 1937 and codenamed “the resident of Buganda” wrote a letter to the chief secretary in Entebbe requesting “permission for Mrs. O.E. De Souza to be an authorised officer”. De Souza was originally of Portuguese nationality from Goa, India.

Goans in Uganda were reported to have been mostly Roman Catholics and hence cut off by religion from their fellow Asians and by race from fellow Ugandans.

She was married to a naturalised British in 1938. Having signed a “Declaration of Acquisition of British Nationality” before a Commissioner for Oaths, she came to be regarded as a citizen of the United Kingdom and Colonies but she was not naturalised in the strictest sense.

The “resident in Buganda” considered her to be thoroughly trustworthy, loyal and discreet since her work had been to his entire satisfaction. He was quite satisfied that she would never divulge any information of any nature which is entrusted to her.

However, the officials in the governor’s office took a different view. They did not question her loyalty or discretion—in fact; these were thought to be beyond reproach. But despite her competence, it was suggested that “Mrs. De Souza should not be ‘authorised’”.

It should be noted that these discussions took on board not just the racial background of the officers but also their nationality, as well as their official status. A draft letter written in late 1961 noted: “On no account should any personal communication be shown to any African, to a person of an- other nationality other than British, or to a non-official”.

The officers in Uganda were conscious of the global repercussions of their work. They believed that the same rules they applied were and had to be shared in London and other British colonies worldwide.

So, why did they have to exclude non-European officers from the operation? Clearly both De Souza and a certain Venkateswaran had been trusted on an individual basis, but now the situation had changed.

A document written later mentioned the possibility of causing offence to anyone of whatever race who may read it! A year later, one of the ministers, most likely of African origin, lodged a complaint about the destruction of records. The response received was that it was only usual practice to destroy documents that had lost value.

The response included the following line: ‘If you have been handicapped by lack of information with regard to any specific subject or district, perhaps you would let me know so that I may ascertain whether you have been correctly informed regarding its destruction.’ On June 16, 1961 it was recorded that the purging of documents “should now have been completed”.

DOCUMENT MIGRATION

However, after burning a large portion of the documents, transporting (migrating) the remaining ones presented another major task. In British eyes, there could be no question of an African courier carrying “D.G.-classified” mail, since it would only take one road accident to the courier’s car, with the dispatches stolen while he was lying injured or unconscious, to create a very inconvenient and undesirable situation.

The challenge was not only to send an enormous amount of documents securely, but also to do it in such a way that those involved in the transportation would have no idea of what they were doing.

Even when the documents were delegated to the Royal Air Force, which shipped them in strong, yet light containers suitable for air transport from Uganda, via Nairobi, to Britain, the officers decided to remain low-key, by deliberately not treating the cargo as classified material.

Although sources reveal the discussions about who were permitted to take part in Operation Legacy, they still left an important question unanswered: how did the authorised officers choose which records to destroy and which to keep secret?

However, one case provided a rare glimpse of the facts of this matter. In January 1962, Stone was sorting out the sensitive records in his office, when he realised that some of the archives would be of immense interest and value to anyone who would come up to write about “the fascinating events of recent times”.

He suggested that the files, which contained a good deal of “dirty” material, should be sent to the Colonial Office back in Britain, and in due course “they might perhaps be used by some historian”.

First, the authorised officers weeded out the files that seemed to contain some sensitive records that might caused trouble if they were to fall into the wrong hands. Second, when they found in those sensitive files something that might be of future use or historical interest, the whole file was sent to London, while the rest were destroyed.

Thus, sensitivity was the first criterion and historical interest was the second. Additionally, the pressures of time and lack of manpower were overriding concerns. A letter issued in June 1961 reads: “Time is pressing and it is essential that we settle these matters one way or the other very soon.”

The feeling of time running out was not just the result of the prospective independence of Uganda but also of the in- creasing “Africanisation” of the British administration in Uganda.

The fear was that, unless they finished sorting out the sensitive records very quickly, it would not be long before information about the scheme fell into the hands of an “unauthorised person”.

So, significant time constraints either perceived or real, were at play. On top of that, there was a notable shortage of manpower. One of the officers in Uganda complained to the Colonial Office: “Even in this office, it took me just about three months’ hard work to ‘purge’ only the current security graded files and we are still in the process of ‘purging’ the records.”

The role of London during this period seems to have been limited. Finally, the next month, the Colonial Office issued a general guideline on the disposal of records.

This guidance went into some detail regarding the selection process, including instructions to destroy files on political intelligence; whatever the security grading, and all correspondence referring to Colonial Office print series.

It also asked for the colonies to submit “a destruction certificate” when purging certain types of materials. However, at the end of the day, weeding out the documents that circulated within the colonies, as opposed to the correspondence with the Colonial Office, had to be left for “local decision at the discretion of the Governor”.

Thus, the regional initiative that came from the British civil service in Africa was accepted as a norm in London and was transmitted elsewhere. Some of the “migrated archives” were recently “newly discovered” and de- classified under the Foreign and Commonwealth Office (FCO) 141 series.

atuhairwe_robert@yahoo.com

Nb

Of course they had to hide their Evil Empire. It is unfortunate that the Africans themselves have evil minds of rule as well.